Why are Psychic TV Tees So Expensive?

Whether you’re a long-time concert tee collector or just dipping your toes into the hobby, Psychic TV is a name you should know. In the world of music, Psychic TV is an enigma—equal parts band, collective, and occult propaganda. With their provocative history, groundbreaking artistry, and surprisingly deep impact on music, art, and fashion, the band has unquestionably earned its cult following and iconic status.

At the heart of this avant-garde collective was the enigmatic Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, a provocateur, artist, and mystic whose life’s work was to dismantle norms, and rebuild them in unexpected ways. Their decades-long work in performance art and subversion elevated them to a near-saintly status, revered as an almost spiritual figure–they could be described as perhaps the thinking man’s GG Allin.

For collectors and connoisseurs of countercultural artifacts, Psychic TV tees hold a near-mythical status. Often priced in the hundreds or thousands, these shirts are more than just memorabilia—they’re wearable pieces of art tied to one of the most bizarre and influential figures in history. But why is Psychic TV so revered? The answer lies in the provocative legacy of their front person and the boundary-pushing work they created.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll delve into Genesis P-Orridge’s life and work, starting this week with an exploration of the artist’s early life, as well as the collectives, friends, and antagonists that formed Psychic TV.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: Innovator and Iconoclast

Born Neil Andrew Megson on February 22, 1950, in Manchester, England, Genesis P-Orridge was a persistent experimenter from the beginning. Raised in a supportive Anglican household, they cultivated an early interest in surrealist art, the occult, and avant-garde literature.

As a teenager, P-Orridge was heavily influenced by the works of Aleister Crowley, William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, and Allen Ginsberg. P-Orridge was drawn to the occult mythology and spiritual philosophy of Crowley, the cut-up, surreal, and discomforting writings of Burroughs, and the free-spirited, experimental, and rebellious nature of the Beats. This school-age reading and interest echoes through their body of artistic work. Before they had left school, they were already challenging societal norms—changing their name, producing underground magazines, organizing happenings, and forming their first artistic collective, WORM.

WORM was formed with a small group of friends P-Orridge had made in the art department of Solihull School in England. The collective organized performance art shows, produced and distributed print media, and recorded and pressed a single album. WORM was inspired by the British free improvisation group AMM and the writings of John Cage, an American music theorist who pioneered electroacoustic music and the non-standard use of musical instruments and objects—a torch P-Orridge would carry for the following fifty years.

P-Orridge briefly attended Hull University, where they won a poetry competition, became involved in radical student politics, and founded a student magazine. The magazine, which eschewed all editorial control and published anything submitted, was shut down after only three issues. The final blow came when it published instructions on how to make a Molotov cocktail.

After dropping out of college in 1969, P-Orridge moved to London and joined a commune called Exploding Galaxy. The group aimed to shatter its members’ conditioning and routines. Members owned nothing, slept in a different bed each night, ate meals at varying times each day, and dressed from a communal chest, never wearing the same item consecutively. However, P-Orridge became disillusioned with the commune, leaving after only eight months, later describing its power dynamics as reminiscent of Orwell’s Animal Farm. Despite their distaste for Exploding Galaxy, their time there profoundly influenced their ongoing exploration of mind and habit.

COUM Transmissions: COUMers of the Youth

In London, P-Orridge’s work matured into the infamous performance art group COUM Transmissions, whose name and symbolism came from psychedelic visions they had on a drive through Wales. COUM was a word without definition, left for the audience to ascribe their own meaning to. Their performances were chaotic, improvised, and included the use of novel and broken instruments. Performances had titles like Thee Fabulous Mutations, Dead Violins and Degradation, and Clockwork Hot Spoiled Acid Test, referencing the works of Ken Kesey and Anthony Burgess.

Even when P-Orridge’s work was at its noisiest and most opaque, it was rich in reference. This effort to recontextualize and explore their influences through collage and cut-up practice is consistent throughout their career, providing glimpses of the artist’s genius and thoughtfulness.

COUM moved into a fruit warehouse, christening it the Ho-Ho Funhouse. Amid a mishmash of artists, musicians, writers, and designers, P-Orridge met Christine Carol Newby, who would become a close collaborator and friend. Newby, adopting the moniker Cosey Fanni Tutti, built props, designed costumes, and participated in COUM’s increasingly theatrical and shocking performances.

Their performances were purposely amateurish, addressing topics such as sex work, serial killers, occultism, and pornography, while integrating shock tactics like mutilation and real sex acts. Shows featured masturbation, the use of double-ended dildos, Tutti inserting lit candles into her vagina, and P-Orridge being flogged and crucified. The spectacle was not just about the audience’s experience but also the press it drew. COUM sought to break as many people as possible from established notions of sex and society.

Throbbing Gristle: Phallic and Seminal

COUM’s productions attracted a variety of responses—negative attention from the police and media, critical acclaim, and grants, as well as two new collaborators: Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson and Chris Carter. P-Orridge, Tutti, Sleazy, and Carter founded the seminal industrial band Throbbing Gristle—slang for an erect penis—on the anniversary of the UK joining World War II.

The band operated separately from COUM with the intention of appealing to an even wider audience. Though Throbbing Gristle never achieved chart success (their best-selling single was Zyklon B Zombie, a reference to the gas chambers of Auschwitz), they coined the term “industrial music” and paved the way for a genre to emerge. Many conventions of industrial music were established by the band, including abrasive, discomforting sounds and performances that directly confronted audiences with harsh imagery and lighting.

COUM’s financial independence from Throbbing Gristle allowed them to maintain their art grants. However, as their work grew increasingly pornographic, they faced mounting scrutiny from police and politicians. In 1975, they were charged with distributing printed material featuring Queen Elizabeth’s face superimposed on nude women. Their 1976 show Prostitution, which included hired strippers, punks, and prostitutes, led to the loss of their government grants. Scottish MP Sir Nicholas Fairbairn infamously called them “wreckers of civilization,” a moniker quickly adopted by tabloids.

This was a period of societal turmoil in the UK, with older generations lashing out against punk and underground culture. Just eight weeks after the Prostitution show, the Sex Pistols appeared on British TV, sparking fear and outrage in the media. Although P-Orridge felt punk was too traditional of a music movement to truly interest them, they inevitably became entangled in the scene. Acme Attractions, the famed London punk and reggae clothing store, paid P-Orridge and Sleazy $60 to assist in their rebranding as Boy London. Boy London, licensed to sell Vivienne Westwood’s Seditionaries-era designs, would go on to be worn by cultural icons ranging from Sid Vicious to Kendrick Lamar.

The Thatcher and Reaganomics era was gaining momentum, promoting a “law and order” brand of conservatism. Amid this societal panic over the perceived fracturing of traditional values, COUM found itself directly in the crosshairs. The collective had recently gained recognition from the British Council, a proselytizing organization that promoted British art and entertainment abroad, and they were preparing COUM for an international tour of North America. However, following front-page newspaper coverage calling for their imprisonment, they lost their funding and were effectively blacklisted from most venues.

After COUM Transmissions lost its grants and dissolved, the organization was restructured into Industrial Records. Throbbing Gristle, the musical offshoot, went on to release three albums. Their final release was a compilation of recordings from William S. Burroughs’ tape archive. P-Orridge and Sleazy traveled to New York to collaborate on Burroughs’ previously unheard sound experiments, resulting in an album featuring collages of field recordings and spoken-word cut-ups.

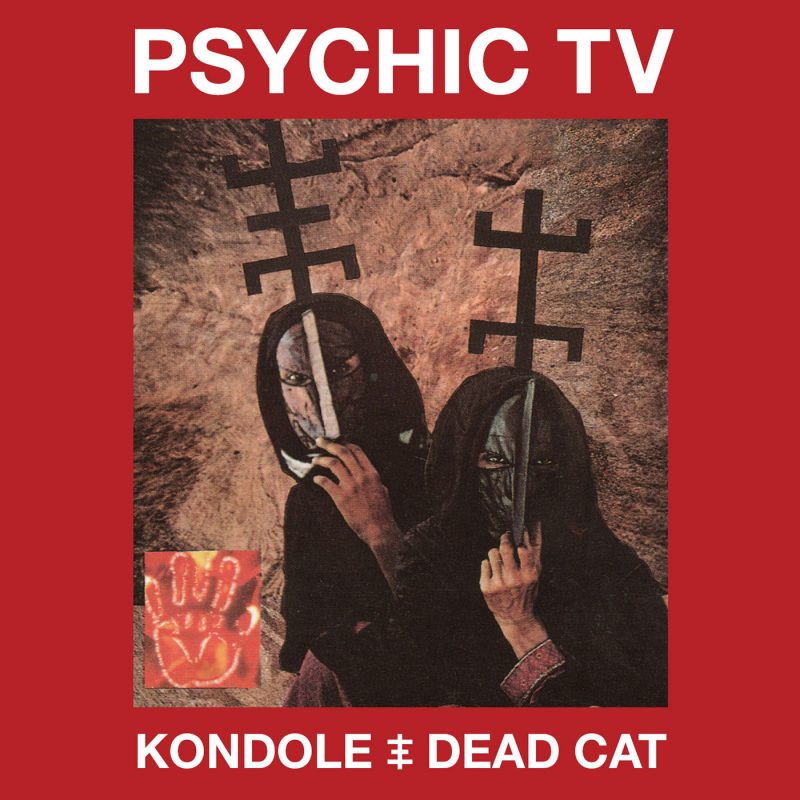

In 1981, P-Orridge and Tutti broke up, Throbbing Gristle broke up, and in the aftermath, a new movement emerged—Psychic TV. This new venture, along with its cult-like fan-club, Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, would merge music, magic, and rebellion into a single vision. Next week, we’ll explore how Psychic TV and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth became the ultimate expression of P-Orridge’s radical philosophy, leaving an indelible mark on culture and consciousness.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment